This is one in a series of profiles marking the 60th anniversary of the ACLU of Kentucky’s founding. Each week through December 2015 we will highlight the story of one member, client, case, board or staff member that has been an integral part of our organization’s rich history.

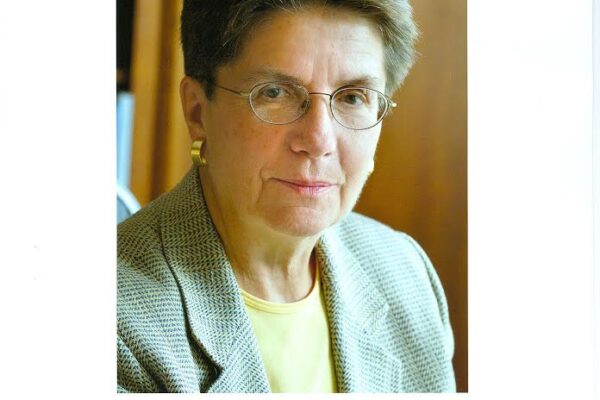

Carolyn Bratt

"You just volunteer. There’s a place for you, it’s wherever your strengths will take you, and the ACLU will use you.” -Carolyn Bratt

When she moved to Lexington to start teaching at the University of Kentucky College of Law, Carolyn Bratt knew that she wanted to be involved in civil liberties work. “I was already involved with the ACLU in New York as a member, and when I came to Kentucky I started looking around to see if there was a chapter,” she said.

Bratt described her civil liberties passion: fighting discrimination on the basis of sex or sexual orientation. Shortly after joining the ACLU in the mid-70s, Bratt spoke to the state legislature about a proposed bill that would criminalize domestic physical abuse. “One of the legislators came up to us and said, ‘Wait a minute. Are you saying that I can’t hit my wife anymore with a belt? I never use the buckle!’” Bratt said. “In 1976 and 78 there was just no understanding of domestic violence, and it took a long time and a lot of education in the legislature to get stuff passed that criminalized that kind of conduct by husbands.” In addition to lobbying, Bratt said she worked with the ACLU-KY and other organizations to establish safe houses for victims of domestic abuse.

Although Bratt was a professor of law, she chose not to work as a cooperating attorney because she was not an active practitioner. In addition to working on briefs and participating in the Kentucky v. Wasson case (which struck down Kentucky’s consensual sodomy statute), Bratt worked on educating Kentuckians about the Constitution.

“We started a project in Lexington with the Lexington ACLU chapter to grow interest in constitutional law,” she explained. Bratt and others created an annual presentation explaining what the Supreme Court had done in its last term. They presented in Lexington, then repeated their presentation in other parts of the state. “At first I was afraid that nobody would show up,” Bratt said. “[But] every year we had a full house. We started out little, maybe 40 or 50 people, and the last year that I did it maybe 150 people came. It showed me that the ACLU was on track with this idea of educating the public. People were interested in getting that information.”